Marta Rojas: The chronicler of Moncada

by Enrique Ojito

reprinted from CubaDebate

July 27, 2016

The texts written by Marta show a high testimonial value. Photo: Vicente Brito/ Escambray.

When on July 27, 1953, the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista moved heaven and earth to capture the survivors of the assault on the Moncada barracks in Santiago de Cuba, including the young lawyer Fidel Castro, leader of the Centennial Generation (La Generación del Centenario), journalism student Marta Rojas took the first flight to Havana to bring to the editorial office of the magazine Bohemia the photographic evidence of the repression committed by the tyranny against the attackers to the second most important military fortress in Cuba. The exceptional witness of the events of July 26 was also preparing to report what happened in her hometown; but the censorship of the press already imposed by the government of the day restricted the publication of the truth of the events that occurred.

Safe

“How important will this be?” asked Santa, the nanny at that guest house in Marianao, Havana, when Marta Rojas, a former tenant, handed her more than 200 typed sheets, with a thousand and one recommendations for their custody.

No one knows if curiosity led the lady to read any line of the report that changed the professional destiny of the young journalist, referring to Case No. 37 of the Emergency Court of Santiago de Cuba for the events of July 26, 1953, ultimately the most transcendental judicial process in the history of the Republic.

That written memory, kept by the nanny as if it were the most coveted ancient papyrus, Marta went to look for it in the early morning of the First of January 1959, at the request of Miguel Ángel Quevedo, director of the magazine Bohemia, while Fulgencio Batista stampeded on a plane to the Dominican Republic, seeing that his tyranny was falling apart. After the assault on the Moncada and Carlos Manuel de Céspedes barracks, in Santiago de Cuba and Bayamo, respectively, press censorship restricted the publication of the report delivered by the young woman in October 1953.

The young woman from Santiago was part of the team of journalists for Bohemia magazine. Photo: Archive.

The more than six elapsed do not take away from Marta Rojas, José Martí National Journalism Award, not a single detail of the historical coverage, which she remembers in her Havana apartment, at the request of Escambray.

The Report of the Shots.

“Are you going for carnivals?” asked photographer Francisco (Panchito) Cano, Bohemia’s graphic correspondent in Santiago de Cuba, to the 23-year-old, who arrived in the city the day before from Havana, where she was studying journalism.

“Yes. I’m going for the Trocha.”

“Do you want to earn 50 pesos?”

Faced with the tempting proposal, the girl returned a question:

“What do I have to do?”

With the agility that he used to tighten the shutter of the camera, Panchito asked her to write a chronicle and captions for the photos about the carnival parties, whose busiest area was the Trocha, usual scene of the crossing of the congas of Los Hoyos and El Tivolí, with all the ardor of the chinese leathers and bugles.

“The merger is coming! Do you hear the Chinese rockets,” Marta alerted him, who had only heard gunshots in western movies.

“No, no; they’re not rockets, those’re shots. Our report of the carnivals is screwed,” Panchito lamented.

“Oh, well. Then we’re going to do the report about the shootings.”

It was past five o’clock in the morning on July 26th; a group of young people, led by lawyer Fidel Castro, was trying to take the Moncada barracks, Cuba’s second largest military fortress, by surprise.

“The soldiers are fighting,” said someone near Marta, and in less than a jiffy she decided to follow the rush to several journalists, who, anxious to know what was really happening, reached the Diario de Cuba, the main newspaper in the city. “Me there and nothing was the same; she was a student, a girl who was not collegiate yet,” she would clarify to Escambray.

With the restlessness still around them, Marta and Panchito arrived at Post 6 of the fortress, where not a few reporters were already waiting to enter, which was only possible after noon that Sunday. With more than one question in hand, the colleagues waited in a room, immediately to the headquarters.

While Colonel Alberto del Río Chaviano, head of the Oriente Military District, was preparing the report that he would disseminate at the press conference, Panchito requested permission to reach the health services; on the way, Marta narrated, he saw two women in a room: Haydée Santamaría and Melba Hernández, the only two people among those arrested at the Saturnino Lora Civil Hospital who survived the criminal debauchery. At the door, the photographer pretended to portray them; on his return, he imposed the novelty on his companion:

“There are two women who are being interrogated.”

“Yes, two women?”

With the doubt on duty, she invented the helpful excuse of going to the bathroom, and thanks to the coordinates given by Panchito, she corroborated that the news of her colleague was not the daughter of hallucinations.

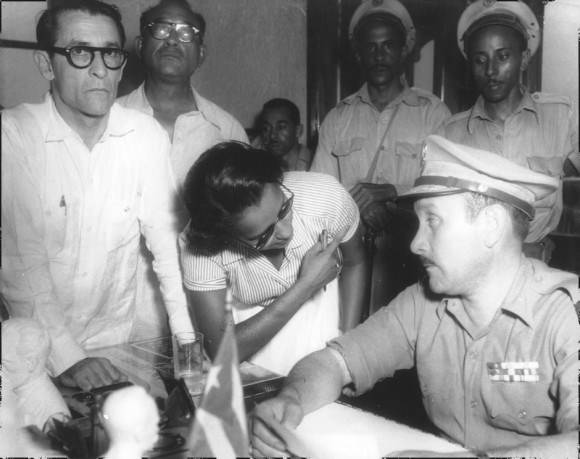

In dialogue with Colonel Chaviano, during the press conference on July 26, 1953. Photo: Archive.

At one o’clock in the afternoon, Chaviano — nicknamed the Jackal of the East — decided to face the press. The only certain thing he said was that Dr. Fidel Castro was the head of the movement; everything else, pure fallacy: that the attackers carried very modern weapons, that Fidel had been paid a million pesos by the people of former President Prío Socarrás…

“Who are the two women prisoners?” asked Marta.

Without recovering from the question at point-blank range, the colonel fixed his plate cap with his right hand almost to his eyes, and maintained authoritatively:

“There are no prisoners here; all died in combat.”

But, a guard alerted something low to the Jackal, who to get out of the trance would be less categorical:

“Maybe, while we were here, they have arrested someone.”

After the exchange with the journalists, they insisted on touring the ground to verify the magnitude of the actions. “They are preparing the scene of events,” Chaviano himself reported.

“How was the scene of the events? In a fight people fell where they fell,” Marta told the photographer in a whisper.

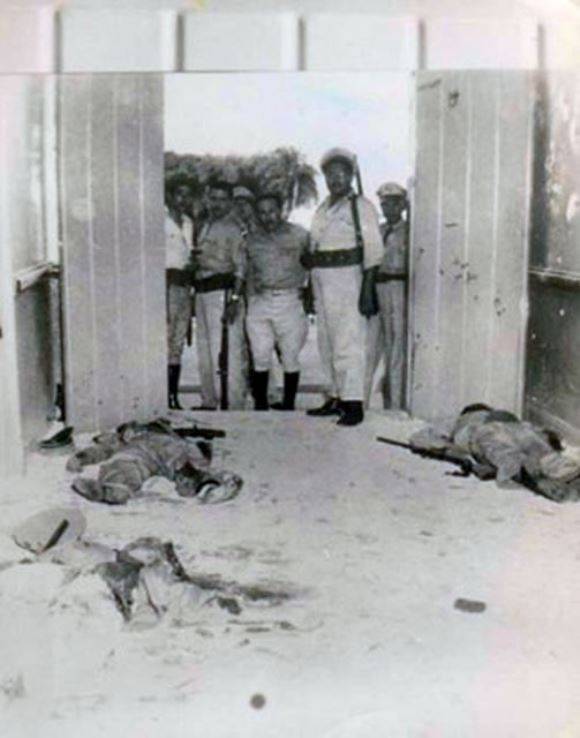

After 6 p.m., they began “a dramatic pilgrimage through the courtyards, stairs and corridors of the Mocada,” she wrote later. Before her eyes, an outstanding scene: corpses without teeth or nails, shot in the forehead; bloody and dying handprints clinging to the wall; half-dressed, the corps in Batista’s army uniforms clean and new… And if that were not enough, the tips of the bayonets of the guards removing the viscera to allow the passage of those who toured the place.

After the assault on the Moncada barracks, more than 50 revolutionaries were assassinated. Photo: Panchito Cano.

After the assault on the Moncada barracks, more than 50 revolutionaries were assassinated. Photo: Panchito Cano.

At the end of the journey, Marta recalls, the reporters remained in the barracks polygon. Minutes later, the Jackal shouted from a staircase: “There are no photos.”

Without a double thought, Cano asked Marta:

“Do you have the photos of the carnivals here?”

Stealthily, they exchanged the films behind a truck. When Chaviano himself requisitioned the camera of the Bohemian correspondent, there was only one unreleased roll; the rest – those taken during the night of July 25 and the early morning of July 26 during the festivities – also went to the huge canvas backpack, which swallowed the trick, which would later ridicule the Jackal before the General Staff of the Batista tyranny.

Marta, exceptional witness to the events of July 26, 1953 in Santiago de Cuba. Photo: Vicente Brito/ Escambray.

Marta, exceptional witness to the events of July 26, 1953 in Santiago de Cuba. Photo: Vicente Brito/ Escambray.

In Search of Accreditation.

Aware of the daring lie and almost without putting their shoes on the asphalt, Marta and Panchito collected the photos of the dead and wounded soldiers in the studio of Lieutenant Senén Carabia, photographer of the Press and Radio Bureau of the Moncada barracks. That same night, the graphic correspondent revealed, in a small dark room on Enramadas Street, the films he delivered, still wet, to Marta, who traveled the next day to Havana on the first flight. Final destination: Editor of the magazine Bohemia. “I’m going to get lost,” Panchito told him.

The information that Quevedo directed the still student of Journalism to elaborate had portrayed her instant death since Marta sat in front of the typewriter; the censor of tyranny was already at the headquarters of the publication, which would barely insert the official note of the General Staff, accompanied by some photos, in its next edition.

“Go immediately to Santiago, because the one they are chasing to kill him is Panchito,” Quevedo suggested, while he put his glasses to rest on the bureau. For any emergency, the director gave her money. “Do your normal life,” he also recommended.

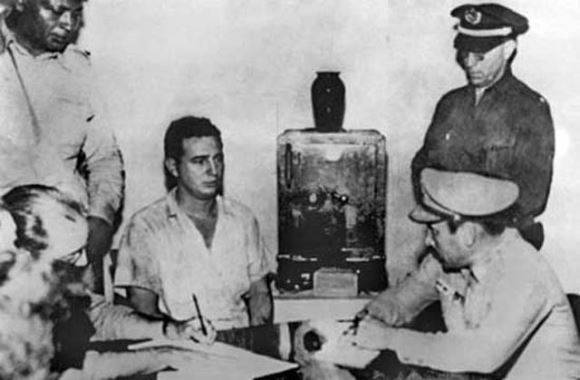

Fidel Castro after being captured, along with other attackers at the Santiago military fortress. Photo: Archive.

Fidel Castro after being captured, along with other attackers at the Santiago military fortress. Photo: Archive.

However, she disrupted her routines, as she said in an interview with this reporter. “I visited the places related to the Moncada: the Granjita Siboney, the hospital; I came to Bayamo, all with the interest of enriching my report to publish it when they suspended censorship. I always went with a little companion or a friend,” she added.

She also frequently began to go to the Emergency Court of Santiago de Cuba to know the date of the start of the trial; the Bohemian Newsroom returned in search of official permission to cover; however, she was not a qualified journalist. Quevedo did not close all the doors to her:

“If you bring me a work, even if it is not published now, I will pay you as a collaborator.”

Back in his city, he looked for the alternative in coordination with the lawyer Baudilio (Bilito) Castellanos, who had made some guayaberas in the tailor shop of Marta’s father and was, in addition, the public defender of almost all the assailants. The elaboration of a report based on interviews with some judges linked to Case No. 37 was the master lunge.

“They’re not going to tell you anything that hurts them. Maybe the censor will pass the job to you,” said Bilito, who had shown up at the Santiago Bivouac upon learning of the arrest of Raul Castro and other attackers.

Certainly, the magistrates, who had sworn in the Constitutional Statutes established by Batista, did not risk their robes, and, therefore, they limited themselves to highlighting technical elements of the criminal process: more than 200 defendants, countless pieces of evidence of conviction… Even Baudilio, Fidel’s companion in the student struggles, spoke of his duties as a public defender.

With the magazine in hand, as a sign of a war trophy, he appeared at the Tribunal. In the midst of the relaxed atmosphere among the lawyers, Marta said to herself: It is now or never, and asked the president:

“Oh, I would like to see that judgment.

The magistrate read again the head of Bohemia and asked the sheriff for a list; when she slid her fist on the leaf, the name was born: Marta Rojas (Bohemia).

Colonel Chaviano interrogates Fidel at the Moncada barracks. Photo: Archive.

Colonel Chaviano interrogates Fidel at the Moncada barracks. Photo: Archive.

A Different Man.

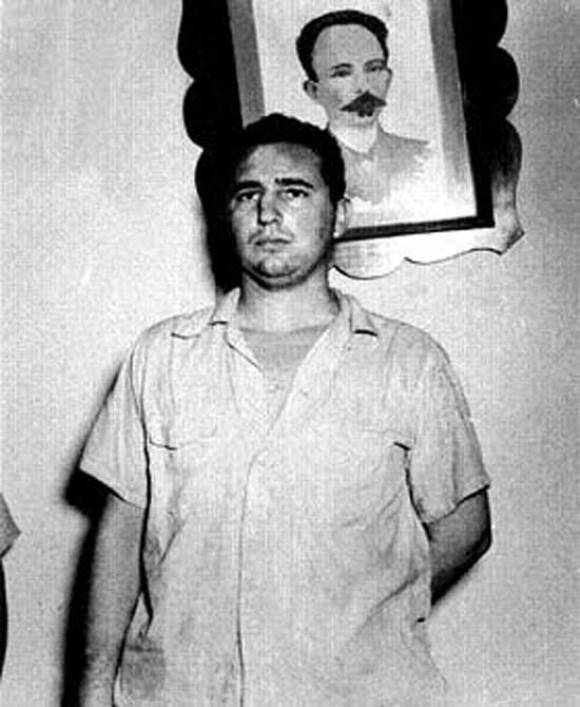

September 21, 1953. Palace of Justice. Wearing a blue suit and red tie, Fidel entered the Plenary Hall, a square besieged by so many bayonets inside and outside the premises; without fear he then clashed the handcuffs who held his hands captive and stretched out his arms as he pointed with them towards the moncadistas.

“Mr. President, ladies and gentlemen, I would like to draw your attention to this unbelievable event! (…), no one like this can be judged, handcuffed.”

“Fidel captivated me from that moment,” Marta said. “It caught my attention because he was a different man. There he was raising his hands, and he managed to get everyone’s handcuffs removed.”

“The hearing is open,” said the president of the Chamber, when it was a quarter of an hour before 11 a.m.

From there, Martha did not stop going one day to the sessions of Cause No. 37; she did not write down in any agenda or notebook; she chose to do it on discrete leaves that she folded in the form of an accordion. On her way home, many people cut her off to inquire about the progress of the trial. Already, at home, she elaborated the report as if it were going to be disseminated the next day. Not a few afternoons she returned to the Tribunal to complete certain information or copy some document, such as the forensic certificates, only mentioned during the oral hearings.

“Rojas, your daughter is wasting her time there; none of that is going to be published. How is she going to miss the opportunity to work in television?,” alerted the father of the young woman, a well-known reporter. Marta desisted from appearing on Channel 2, of the TV, where she was supposed to start working in September, and, after the first stage of the judicial process on October 2, she continued to frequent the hearing to know the date of the announcement of the trial against Fidel. The leader of the movement remained detained in the Boniato prison, deprived of attending it since the third session because he was “sick”, according to the prison’s medical staff.

Fidel at the Bivouac in Santiago de Cuba. Photo: Archive.

Fidel at the Bivouac in Santiago de Cuba. Photo: Archive.

Alerted by Bilito that the oral hearing was almost imminent, on October 16 the young woman went again to the judicial institution, where she was surprised by the announcement: “First Room. Cause 37, transferred to the Civil Hospital.” To get on time, there was only one option: run. Luckily, the place was across the street. At the door, the Military Police, “unfriendly and petulant”, stopped Marta in her tracks, who entered thanks to the intervention of the prosecutor Mendieta Hechavarría.

With her eyes, tamed by curiosity, and from her scissor chair, she noticed in every detail the rabid atmosphere of the nurses’ room, headquarters of the trial: showcases with skeleton and books, two desks, a portrait of Florence Nightingale, a small table and a chair for Fidel, who arrived sweaty, dressed in his blue suit.

“It’s a pity that having such a nice new Palace of Justice you have to come and work here.”

Marta saw a smile drawn on the prosecutor, “which was rather a grimace”, and wrote down as much as she could of each judicial procedure. Among the witnesses, Commander Andrés Pérez Chaumont, appointed by Chaviano as head of the revolutionaries’ capture operations, who was questioned by Fidel:

“And how do you explain that there were no wounded in our group, but only deaths… Did you use atomic weapons?

The question of the insurrectionary leader was only an indication of his subsequent allegation, later recognized as History Will Absolve Me, where every word was an axe to so much crime, to so much wounded and corrupt republic.

Because “he spoke a different language,” as the author of The Moncada Trial wrote, the guards, the hospital employees… Everyone listened to the self-defense, more than two hours long, in a silence never heard before.

Almost without deliberation, the Court ruled 15 years in prison. The accused, turned accuser, was not surprised by the conviction, and serenely looked at his watch: one in the afternoon.

Marta Rojas, together with Haydée Santamaría and Melba Hernández. Photo: Archive.

Marta Rojas, together with Haydée Santamaría and Melba Hernández. Photo: Archive.

Censorship and…

The next day, Marta traveled to Havana with the same final stop: Bohemia, and exclusivity already in the suitcase: more than 200 sheets, historical testimony of an exceptional event.

“That mammoth!” If they suspend censorship and put that in, it’s the only thing we would publish, Quevedo told him, without pejorative nuance.

Once the constitutional guarantees were restored and the information quarantine suspended, Marta wrote a 12-page version, inserted almost five years later in the section En Cuba, in Bohemia, of whose journalistic team this Santiago was part.

As soon as Batista set foot in dust, the press organ disseminated, first, two graphic pages and, then, a series of reports from that original, today yellowish and true relic, collected by the journalist in the early morning of the First of January in the guest house of Marianao.

“Look, these blue strokes were to cross out and censor this part where Fidel speaks,” Marta told me, who went to meet the leader of the Centennial Generation in the company of Melba and Haydée, after his departure from the Presidio Modelo, then Isla de Pinos. On the day of the visit, she, fond of hand psychology at the time, predicted the future to Fidel:

“I’m going to see you with a white beard.”

Marta rereads her original writings in 1953. Photo: Vicente Brito/ Escambray.

Marta rereads her original writings in 1953. Photo: Vicente Brito/ Escambray.